Churchill Wild’s Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge is the best place on the planet to view and photograph wild wolves (and polar bears) and the whole world will soon know it.

Last November, New York Times best-selling novelist Peter Heller (The Dog Stars, The River, The Guide) and his wife, actor Kim Yan, joined us on the first-ever Cloud Wolves of the Kaska Coast citizen-science wolf expedition. Heller was on assignment for Condé Nast Traveler.

“This was one of our favorite trips ever,” said Heller. “We had loved seeing wolves in Yellowstone National Park. But there they are so far away, just little specs in a spotting scope. Here, on our very first day, a wolf walked right up to our group. It was incredible.”

Heller’s wonderful feature story from the trip, On Canada’s Remote Kaska Coast, Wolf Spotting Under the Northern Lights, illustrated by National Geographic photojournalist and Churchill Wild Director of Wolf Programs Jad Davenport, appeared in the September/October 2022 issue of Condé Nast Traveler, a special 35th Anniversary Edition entitled The Future of Travel. It’s on newsstands now, and it’s a vivid and beautiful read.

Award-winning outdoor travel journalist Robert Annis was also at Nanuk for the last Cloud Wolves of the Kaska Coast adventure, and wrote a feature for Departures Magazine entitled In the Company of Wolves. Getting up close and personal with North America’s alpha predator.

“Although we have multiple close encounters with the Opoyastin pack, one in particular sticks out in my mind,” writes Annis. “After watching the pack slumber on the ice — the reflective surface of the ice actually helps warm them — we move on until spotting a dark fleck on the horizon. We stop and watch as the fleck stirs, and then begins walking toward us.

“I expect the wolf to veer off, but Lip Lip — so named because of a scar on his muzzle — walks up to within just feet of us, his inquisitive nature shining through. We all stand motionless, trying not to spook him. If a wolf could look like he was ordered directly from central casting, it’s Lip Lip — thick, gorgeous fur that’s beige, black, and white; wide muzzle; deep hazel eyes.”

“There is no better place in the world to photograph wolves than Nanuk,” said Davenport. “Nanuk’s cloud wolves have never been hunted, they have no fear of humans. I’ve photographed wolves in Yellowstone, Denali and the Yukon, but the encounters there are distant, and you’re usually shoulder-to-shoulder with dozens and dozens of other people. It doesn’t feel wild.

“At Nanuk it’s just you and your fellow guests watching the wolves hunt, play, court and, of course, howl, often right in front of the lodge. It’s the only place I’ve ever had wolves approach me when I was on foot and get to within a few metres. I had to shoot photos with a wide-angle lens. That never happens anywhere else.”

The idea for the Cloud Wolves of the Kaska Coast safari naturally developed after a number of wolf encounters at Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge. Davenport started leading trips at Churchill Wild 10 years ago and had seen the wolves on a number of different safaris including the Den Emergence Quest, Birds, Bears and Belugas and the Hudson Bay Odyssey.

“We kept seeing a lot of wolves,” said Davenport. “And the guests just loved them. We started realizing, wow, this is exciting. And the Kaska Coast is really the only place in the planet that we know of right now where wolves cross range with polar bears on land. In most places their ranges just don’t overlap. So we’ve got this apex marine predator, the polar bear, and the terrestrial predator, the wolf, together in one place.

“These wolves have never been studied. The area is too remote. And it’s a wilderness the size of California. Nobody knows anything about the wolves up here, so we took some advice from biologists and decided to set the trip up as a citizen science field study where guests can participate. And they’ve really taken to it.

“We go out and look for the wolves when we’re there. We track them and try to interpret the tracks and figure out where they’re heading and where they’ve been. We set up trail cameras in certain grids to see if they’re moving along the rivers. We collect scat. We’re going to start doing DNA analysis. We haven’t even gotten to that yet because we’ve been so busy with direct observation of the wolves and we’ve got so many questions to answer.

“We’re watching them and following them from a distance, trying to figure out what they are doing. How many packs are there in the area? How big are they? What are they feeding on?”

Polar bears are not expected to be part of the agenda on either the March or November wolf safaris, but sometimes they just show up, as they did for National Geographic filmmaker Bertie Gregory at Nanuk in Wolf Pack Takes on a Polar Bear – Episode 1 | Wildlife: The Big Freeze.

“We don’t anticipate polar bears being there at that time of year,” said Davenport. “We tell people not to plan to see them, but it is possible, and it does happen, so we do take precautions. And if they are there, of course we’re fascinated to see what happens. I mean, we were able to observe polar bears and wolves interacting on the very first expedition, so that that was fascinating. And it was fantastic when Pete Heller was there. Every time we went out the door, we were having to deal with a polar bear.

“But really, people should be coming on this trip to see wolves and participate in the citizen science. And every guest has something different to contribute.”

Guests to date have included a veterinarian from Washington talking about observing the wolves for any type of parasites and taking photos of their teeth to determine how old they were; a surgeon from Ontario who showed the group how to use scalpels to slice up scat for DNA analysis; a rancher from Montana who gave a talk on how he maintains balance between his herd of cattle and the local wolf pack without having to kill any of the wolves; a computer programmer and a statistician from Switzerland who was talking about computer modeling; a musician who had some suggestions for bioacoustics; and a mother and her son from Singapore who was a tech wizard at setting up trail cams.

“He just embraced it right away,” said Davenport. “And his mother was a very refined lady, yet she was out their combing through the moose carcass.

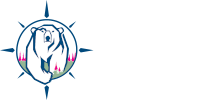

“The groups have been fantastic so far. They’ve just gelled instantly. It’s not just me saying here’s what we know, it’s all of us with maps and photos spread out on the table, deciding where we should go the next day based on what we’ve seen so far. Comparing photos of different wolves, their characteristics, looks and behaviour, trying to identify the individuals. Everyone became citizen scientists for the whole trip, without any prompting. So it was exciting for me.

“They’re helping do something. It’s not just sitting on the snow machines and taking pictures. If the wolves aren’t there, we have tons to do. And we’re teaching the guests survival skills too. We built an igloo. We showed them how to build fires without matches. They loved it. It’s fun for them.

“We set up the trail cameras. We have to go out and collect the cards. We’re finding out where the wolves have been, where the new sites are, and we’re trying to map those out. It’s a lot of fieldwork. For anybody that wants to have the experience of being a wolf naturalist in the field, that likes to get out and get involved, it’s perfect.

“Everybody has a strength that we don’t have, and we draw on their talents and whatever knowledge they have to help make the group stronger.”

While Churchill Wild and Davenport can’t guarantee wolf sightings at Nanuk, the first four cloud wolf trips and other related safaris have all resulted in sightings and often in close encounters. And when the opportunities present themselves, you really can’t get this close to wolves anywhere else in the world.

The average viewing distance of a wolf in Yellowstone National Park is over two kilometres and probably closer to three. You’re often looking through a spotting scope at little black dots in the distance. Most tour operators running wolf trips state in their disclaimers that wolves may only be spotted at a distance if at all. There have been numerous field studies done on wolves over the decades, but never on the Kaska Coast of Hudson Bay. And never using citizen science at close range.

Guests might spend a whole day in the field on snowmobiles and riding in komatiks following a pack without seeing them and then…

“At the end of six hours, we come up over a ridge and there they were,” said Davenport. “And it was thrilling. There were 14 wolves. We had been out the whole day and everyone was out looking at the tracks. So it wasn’t as though we knew where the wolves were going. This wasn’t something where you say we’re going to drive 20 minutes and then sit and watch wolves. These wolves can range for hundreds of miles. it was a true tracking experience. It’s a fantastic adventure.

“It’s wild and remote and the weather can be harsh. It’s not like strolling around in the summer. We’re out there in blizzards and we’re moving around. It’s the real deal. And when you’ve got polar bears around…

“On each trip we’ve had some fantastic encounters with wolves. We found the pack, we stayed with them and then the wolves eventually got up, came over and kind of investigated us. I think in the very first one, the wolf was probably two metres away from people. It was a lone wolf that walked over and circled the group a couple of times, looked at everybody and then went and told his buddies who and where we were.

“We also had a trail camera set up on a kill, where they had taken down a moose. And we take a look at the social dynamics of the animals. We’re trying to figure out the relationships of the wolves to each other? The family units. And which is the breeding male and which is the breeding female. There’s typically only one breeding pair in a pack. It’s little things we look for, like raised tails, things like that, information you can only get by being in the field and documenting it.”

The work being done in the field with the wolves will eventually be turned into an annual report. Davenport is already working with biologists and other wolf groups, and he’ll also be presenting at the International Wolf Symposium in Minneapolis.

“And of course there’s the lodge,” said Davenport. “There’s nothing like coming back from a hike to a roaring fire in the great room, dinner of cranberry glazed turkey and a bottle of Merlot, and enjoying a hot shower back in your room.

“There’s no place like Nanuk in all of the Arctic.”

I was by the fire one morning and Butch said, ‘wolves are coming.’ Suddenly, there were four wolves. They came right up beside the window. They weren’t galloping past, they were walking slowly. They gathered right on the snowdrift and looked inside at us. It was unreal. I wanted to cry, it was such an emotional moment to see them so close. — 2018 and 2020 Churchill Wild guest Sue Chadwick, UK

After a long and exciting day on the snowmobile/komatik we made our way back towards the cozy warmth of Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge. Just before arriving, we spotted a wolf not far away. She started howling. Instantly, the other members of the pack joined her beautiful and chilling song. Later, the female leader of the pack trotted towards us. She came within a few feet of our komatik, then stopped and looked directly into my eyes. She was neither aggressive nor afraid, just curious. I had tears in my eyes—and I still do, when I think back to this wonderful encounter. — Arctic Wild Photographer (five-time guest) Fabienne Jansen, Switzerland

There are still a few spots open in this year’s remaining wolf expeditions in November and next March, but we expect these to fill quickly. If you’re on the fence and want to join us for an exciting chance to watch and study the wild cloud wolves, reserve your spot today.