Introduction

Welcome to the 2025 edition of the Cloud Wolves of the Kaska Coast newsletter where you can read about this year’s expeditions and findings and get the latest updates on our work and wolf science and natural history. This year marks the wolf program’s fourth year; in November we celebrate our 17th and 18th cloud wolf expeditions at Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge.

Over the past four years the wolf program and our wolves have attracted international media attention in National Geographic, Canadian Geographic and other magazines, and been featured in several television documentaries.

As Churchill Wild continues to become known as the THE place to encounter and photograph wild wolves, we are expanding our program to include a summer expedition in July 2026 where we will search for and hopefully find a wolf rendezvous site—a homesite wolf pups inhabit after leaving their natal dens.

For guests who opt to participate in our citizen science work—traditional field observations of wolves, the use of trail cameras and investigation of kill sites—we are pleased that our contributions to science continue to be made available to international biologist. In the past 12 months our work has been featured at the Great Lakes Wolf Symposium in Wisconsin and in a feature article in International Wolf Magazine, the quarterly publication of the International Wolf Center, the leading science-based wolf education center in the world.

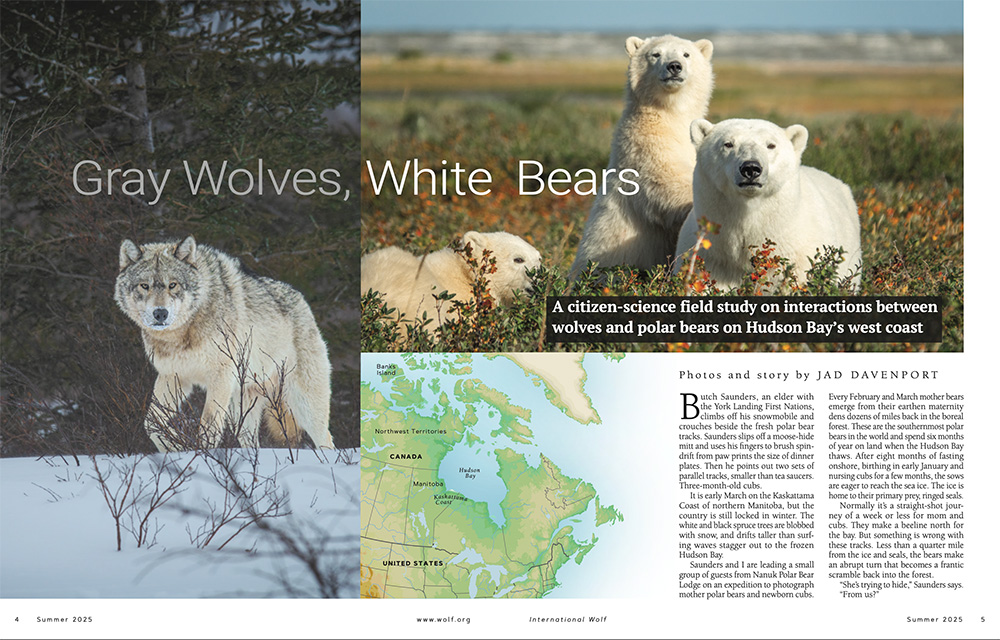

A citizen-science field study on interactions between wolves and polar bears on Hudson’s Bay west coast by Jad Davenport.

Status of the Pack

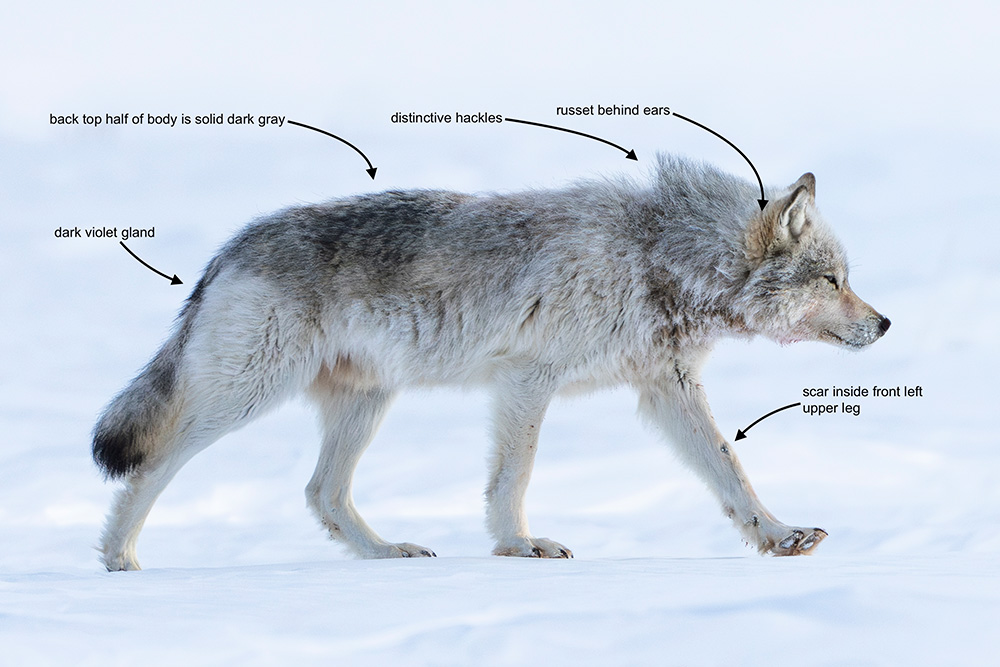

After a rough start last year when the Opoyastin Pack, down to five members, failed to raise a surviving litter and faced off against the 12-strong Kaskattama Pack, there was welcome news this spring when six pups were born to the breeding female, Nikah (“mother” in Swampy Cree) and the breeding male, Mestakaya (“big hair).

We were informed of their births through friends at the York Landing First Nation who filmed and documented the wolf pack at their new den near Ten Shilling Creek, roughly 46 km south and west of Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge.

Several members of the band were caretaking at their season goose and moose-hunting camp and filmed and photographed the pups and several adults. Only three adults were seen—Mestakaya and Nikah and Kasisi (“scratchy”), a stepdaughter. According to the caretakers both Nikah and Kasisi appeared to be nursing the pups.

Based on the videos and photographs and the pups’ physical development, the litter was born on May 1. By early June all six pups were still alive.

Jad Davenport, Churchill Wild director of wolf programs, and Chris Paetkau of Build Studios and Arctic Films (a cooperative film unit with Churchill Wild), helicoptered into the site and spent several weeks trying to discover what happened to the wolves and their new litter. Jad and Chris scoured more than 16-square kilometers of the surrounding boreal forest by foot, ATV and drones and did aerial searching by helicopter from Ten Shilling to Cape Tatnam in the far northeast. Ground searches proved challenging due to the swampy nature of the muskeg and the dense, tangled growth of black spruce forests, but the drones proved excellent for spotting wildlife from the air.

Both females, Nikah and Kasisi were found and filmed on several occasions. Both looked healthy and appeared relaxed. The pups and Mestakaya, however, were not seen. The camp caretakers had expressed concern that Mestakaya was limping from a rear leg injury, possibly the result of a kick from a moose, but he appeared to be putting more of his weight on the leg at the time he vanished.

Aerial view of Ten Shilling camp.

The Vanishing Litter

The majority of wolf pups don’t survive their first six months; starvation and predation from other wolves and bears, and even raptors, are all hazards.

Both a polar bear and two black bears were filmed in the vicinity of the den, with the black bear investigating the den opening. It is possible that while mom and dad were away from the den the pups were killed and eaten by a bear.

During the time the litter vanished biting arctic insect populations were booming, particularly black flies, mosquitoes and horse flies. Because the den was exposed, it’s also possible the mom moved the pups to a secondary, earthen den where they might have some respite. Wolves have been recorded moving pups to secondary dens as far as 20 miles from the original natal dens. While Jad and Chris did a number of howl surveys and searched potential den sites by foot and drone, no sign of the young pups was found.

Wolves have also been observed to move litters if the natal den becomes overly infested with fleas. While no fleas were observed in and around the den, it’s possible this could have also played a role in the disappearance.

If some or all of the pups have in fact survived, we expect that our summer guests might be lucky enough to glimpse them in July and August.

Lessons Learned

Exploring the Ten Shilling and Hayes River delta was a unique opportunity for Jad and Chris. They documented abundant wildlife including polar and black bears, caribou, moose, beaver, river otters, bald eagles and waterfowl.

From scat around the natal den it appears the wolves had been predating on both beaver (as evidenced through fur in the scat) and moose. The severed leg of a newborn moose was found immediately outside the den.

The Opoyastin Wolves have been reported regularly to the wolf program by members of the York Landing Community during their hunts at Ten Shilling and it is clear the area provides an excellent prey base with vast moose and beaver habitat.

In the past the Opoyastin Wolves have ranged from the tip of Cape Tatnam (43 km north and east of Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge) to Ten Shilling Creek (46 km south and west). Last year the Kaskattama Pack (found from Cape Tatnam to the Ontario border) attempted to encroach west into the Opoyastin Pack’s territory. Observations this summer and on the fall Cloud Wolf Expedition will hopefully shed more light on whether the wolf pack territories are shifting.

The Den

The den itself was dug out by the wolves beneath a shed used to store snowmobiles. The den had two entrances—southern and northern entrances—and extended beneath the entire, raised structure. The immediate area of the den was littered with bone scraps, antler pieces, feathers and other toys. It was possible, due to the exposed nature of the structure, to view completely through both entrances of the den.

According to the caretaker at Ten Shilling, this is the first time the wolves have denned in that location.

Other Local Packs

Based on information from First Nations friends, local pilots and people living in surrounding communities we have compiled a map of six wolf packs between Seal River Heritage Lodge and Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge.

Packs are named after First Nation geographic locations within their territories. The map is a work-in-progress and changes over time as wolf packs grow, shrink and shift territories each year.

For the first time, wolves were seen regularly around Dymond Lake Ecolodge, though they were not as tolerant of humans as the Nanuk wolves.

March 2025 Expedition

Both March Cloud Wolf Expeditions were successful in locating and spending time with both the Opoyastin Wolf Pack and several ‘floater’ wolves.

In March, sightings and trail cameras confirmed there were a total of five members of the Opoyastin Pack.

- Mestakaya (“big hair”), the breeding male;

- Nikah (“mother”), the breeding female;

- Kasisi (“scratchy”), a daughter of Mestakaya and his former mate, Maniway (“cheeks”);

- Makehsis (“foxy”), a subadult, unrelated female,

- Osawi (“brown”), an adult male.

There were four additional wolves documented in the area. These included:

- Kaski (“pitch black”), black wolf, an adult female;

- Tipisk (“night”), black wolf, unknown sex;

- Tawny wolf 1, unknown sex;

- Tawny wolf 2, unknown sex.

Kaski, the most curious of the wolves, spent time around Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge and ventured far to the east. She had several relaxed, close-encounters with guides and guests while traveling on her own.

The other black wolf and the two gray wolves, kept their distance but were observed playing together out on the frozen tundra. It’s possible they are litter mates.

One of the more exciting wildlife viewing opportunities came with the discovery of a kill site. Near the Fourteens, a series of small creeks, the wolves killed a cow moose. After observing the pack on the kill, guides and guests returned to find a young wolverine busy caching bits of the kill.

Wolf Reproduction

Wolf pups at Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge. Tammy Kokjohn photo.

Gray wolf (Canis lupus) breeding in North America occurs once a year, typically between late winter and early spring. Past Churchill Wild expeditions have documented wolves mating around the middle of March.

Gestation lasts 63 days and litters range from four to ten pups, with average size of five to seven, depending on prey availability and maternal condition. Pup development stages:

- Birth (0–2 weeks): Pups weigh approximately 0.5 kg and depend on maternal nursing.

- Eyes and ears open (2 weeks): Pups emerge from the den and begin exploring the immediate vicinity.

- Weaning (6–8 weeks): Pups transition from regurgitated meat to independent feeding and engage in play to develops social and hunting skills.

- Den abandonment (10-12 weeks): Pups are moved from their natal dens to rendezvous sites, usually open areas near water with nearby cover.

- Dispersal (autumn): Subadults join pack hunts and may disperse to establish new territories.

Den Site Selection

Female wolves generally select dens based on drainage, thermal regulation, concealment, and proximity to prey. This often translates to south-facing slopes (to ensure snow is melted from entrances), well-drained uplands (to prevent flooding), and natural cavities. Den entrance modification includes enlarging cavities, packing tunnel walls, and clearing sediment.

Other Wolf Dens

The wolf program has identified a total of five wolf den sites based on oral histories from hunters and lodge staff and a government telemetry study. These are dens that have been used in the past. Three of the sites were checked this summer and only one showed signs of current use.

Citizen Science

Wolves in fall colours at Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge. Albert Saunders photo.

Citizen science has a strong history in North America that stretches back more than a century to the first Audubon Christmas Bird Counts (established in 1900) and today includes modern platforms like eBird and iNaturalist. Field-based observations document seasonal, habitat, and geographic variation in animal behavior, provide additional context for laboratory findings and can help reveal long-term trends unobservable in controlled settings.

The Wolf Programs with Churchill Wild have a citizen-science component that complements traditional scientific research by providing observations that otherwise might not be possible due to limitations on wolf research funding and field time. The staff and guests at Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge have the opportunity, if they chose, to spend extended time in the field observing and recording wolves and wolf behavior from July through December and March through February.

Guests participating in the Cloud Wolves Citizen Science project at Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge. Jad Davenport photo.

Observations can take the form of written notes, digital images and digital video. Guides and guests have also measured, logged and made casts of wolf tracks.

While we have made efforts in the past to include more traditional scientific inquiry (microscopic studies of wolf scat, recording howls) the challenges of providing an appropriate laboratory setting has made us focus instead of traditional field observations—searching for and documenting wolf kill sites and, when possible, filming, photographing and observing wolf behavior.

Trail Cameras

Trail cameras have proved to be an excellent tool for studying the wolves in the field. These motion-activated remote cameras allow us to capture digital still images and videos of the wolves as they move through the landscape or spend time around kills.

We have been using a variety of Browning trail cameras including the Browning Spec Ops Elite HP5 and Dark Ops Extreme cameras.

Learning best practices with trail cameras took several expeditions. Camera placement (wolf eye-level) proved important as did camera aspect (cameras facing directly into the sunrise or sunset captured poor video). We also learned how to select areas that were clear of growth susceptible to wind movement.

The biggest challenge has been how to protect the cameras from the wolves. Wolves destroyed no fewer than six cameras in the first few years, including an instance where they removed a camera strapped to a tree and dragged it several hundred meters before depositing it in the ice hole we pump water out of in the winter.

First Nation elder and guide Butch Saunders recommended wrapping the cameras lightly in wire saying wolves would not like the taste of the metal. Since adopting Butch’s inexpensive and simple solution our cameras have a 100% survival rate.

Trophic Cascades

Wolves at rendezvous site. Nanuk Polar Bear Lodge. Christoph Jansen / ArcticWild.net photo.

It became popular during the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park for researchers to discuss the phenomenon of Trophic Cascade. This describe indirect ecosystem effects initiated by changes in predator populations.

Trophic cascades are generally fueled by either top-down control—predator presence reduces herbivore abundance and alters herbivore behavior, allowing for vegetation recovery, or manifest as bottom-up control in which prey abundance influences predator populations.

Wolf reintroduction to Yellowstone (1995–1996) led to elk population reduction which in turn led to riparian vegetation recovery, beaver population increase, and subsequent hydrological changes affecting stream flow and habitat complexity.

One of the questions our wolf study seeks to answer is how wolves are impacting the environment along the Kaskattama Coast. Does the abundance of moose habitat and moose lead to an abundance of wolves? Does the presence of wolves in the area keep moose and beaver populations in check and thereby prevent the many creeks and rivers from become choked with beaver dams?

As part of our citizen-science study, we distribute information we learn during our expeditions to wolf biologists and the general public. This is primarily done through this newsletter, peer-to-peer communication with wolf biologists, presentations at conferences and guest speakers on podcasts and at special events.

In October 2024, Jad gave a presentation on our study at the Great Lakes Wolf Symposium, an annual meeting of US and Canadian wildlife managers, researchers, tribal biologists, educators and wolf naturalists. The symposium was held at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin.

In addition to Jad’s talk, other presentations addressed wolf population status updates and recovery challenges, various coexistence and deterrent technologies and strategies and a discussion of public attitudes towards wolves.

Jad has also spoken about the field research on podcasts including the February Wildlife Wire Podcast, episode 8, and the Find Your Wild Podcast, Episode 55 in June.

Jad’s feature story, “Gray Wolves, White Bears: A citizen-science field study on interactions between wolves and polar bears on Hudson Bay’s west coast,” appeared in the Spring issue of International Wolf Magazine, a quarterly publication of the International Wolf Center in Ely, Minnesota. The story discussed the origins of the field study during early Den Emergence Quest safaris, to its current form as the Cloud Wolves of the Kaska Coast Expeditions.

During the first part of 2025 Jad gave several talks on wolves at the Explorers Club Western Chapter.

The International Wolf Center (IWC) is a science-based wolf education center and resource in Ely, Minnesota. It was founded back in the mid-1980s by Dr. Dave Mech, the godfather of wolf studies, and a dedicated group of wolf enthusiasts. The center sponsors the International Wolf Symposium, which is held every four years, a gathering of hundreds of researchers, biologists and naturalists from around the world.

The International Wolf Center (IWC) is a science-based wolf education center and resource in Ely, Minnesota. It was founded back in the mid-1980s by Dr. Dave Mech, the godfather of wolf studies, and a dedicated group of wolf enthusiasts. The center sponsors the International Wolf Symposium, which is held every four years, a gathering of hundreds of researchers, biologists and naturalists from around the world.

When you join the IWC (memberships start at $60) not only are you supporting wolf education and investing in a world where humans and wolves coexist, you also receive their beautiful magazine with feature and news articles. And you can visit the center and see and learn about wolves up close in a natural setting.

Do Wolves Need Wilderness?

As the Opoyastin Wolves have proved by denning right in the heart of a hunting camp, it turns out wolves do not require large swathes of wilderness. Many wolves around the world, including in India and Europe, coexist with humans and inhabit ranges that encompass urban areas.

In the Netherlands, one of the most densely populated nations in Europe, wolve have made a remarkable comeback.

Since 2015, wolves have recolonized forest fragments via wildlife corridors. By mid-2024, nine packs (104–124 individuals) were documented. Territories center on large forested areas and riparian buffers along farmland. Wolves use underpasses and adjust activity to minimize human encounters. Conflict mitigation includes electrified fencing, guardian dogs, and compensation programs under the 2019 Interprovincial Wolf Plan.

Wolf Reintroduction to Colorado

Wolves have been making news again in the United States. The state of Colorado voted to reintroduce wolves (they had been exterminated by the 1940s) in 2023, though small populations of wolves had been naturally moving into the state from existent populations in neighboring Wyoming.

Key milestones:

- December 2023: Translocation of ten wolves from Oregon to Grand and Summit counties.

- January 2025: Release of fifteen wolves from British Columbia into Eagle and Pitkin counties.

As of June 2025, pup production was confirmed. Radio-collar data indicate expansion into adjacent watersheds, including Jackson and Moffat counties. Livestock depredation events triggered compensation and testing of deterrent measures.

State of Wolves in Canada

While wolves are considered endangered in the Lower 48 U.S. States, wolves in Canada are not threatened. There is an estimated population of 60,000 wolves across the country.

Provincial estimates:

- Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Yukon: ~5,000 each

- British Columbia: 8,500

- Alberta: 7,000

- Saskatchewan: 4,300

- Manitoba: 4,000–6,000

- Ontario: 9,000

- Quebec: 7,000

- Labrador: 2,000

Wolves are classified as big game; harvest seasons and bag limits vary by jurisdiction. The eastern subspecies—it’s a hot debate whether or not the subspecies is a separate endangered species–holds a Special Concern status under the Species at Risk Act.

Did We Really Bring Back the Dire Wolves?

Back in 2022 Churchill Wild CEO Adam Pauls and Jad Davenport had several meetings with scientists from Texas-based Colossal Biosciences. The scientists had attended the International Wolf Symposium where Jad spoke about our citizen-science program.

The company was interested in Churchill Wild’s wolf programs, particularly in our access to an unstudied wolf population. They inquired about retrieving DNA from the Opoyastin Wolves as they attempted to bio-engineer extinct dire wolves.

If the name sounds familiar, that’s because Colossal made headlines recently by announcing the birth of Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi—three pups engineered to exhibit traits of the long-extinct dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus). According to Colossal, these animals represent the first “de-extincted” dire wolves in over 10,000 years, generated via advanced CRISPR-based gene editing rather than by cloning or direct insertion of ancient DNA. The company positions the Dire Wolf De-Extinction Project as a proof of concept for rescuing endangered species and advancing conservation technology, aligning its work with IUCN SSC guidelines for creating proxies of extinct animals.

Underpinning the project is a multi-step scientific workflow. First, researchers sequenced fragmentary dire wolf DNA from Ice Age fossils—specifically a 13,000-year-old tooth from Ohio and a 72,000-year-old ear bone from Idaho—to identify roughly twenty genetic differences across fourteen genes that distinguish dire wolves from modern gray wolves. They then isolated endothelial progenitor cells from living gray wolves, edited those cells to incorporate the identified variants (plus a handful of coat-color edits), and used the modified nuclei to create embryos via somatic cell nuclear transfer. Surrogate domestic dogs carried the embryos to term, yielding pups engineered to exhibit larger body size, wider skulls, pale coats, and distinctive craniofacial morphology reminiscent of dire wolves.

However, despite the company’s marketing rhetoric, independent experts emphasize that these gene-edited animals are not true dire wolves but rather phenotypic approximations or “proxies.” No intact ancient dire wolf genome was ever resurrected; instead, Colossal relied on fragmentary sequence data and applied most edits to existing gray wolf genomes.

As Colossal’s own chief scientist, Beth Shapiro, later clarified, the animals are “gray wolves with 20 edits,” and the use of the term “dire wolf” has always been a colloquialism rather than a scientific designation. Similarly, the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Canid Specialist Group concluded that these engineered wolves do not meet criteria for proxies under the SSC guidelines, arguing that they lack ecological function, genuine genetic continuity, and the capacity to restore lost ecosystem roles.

The debate over Colossal’s project highlights broader questions in de-extinction science. While the company undoubtedly demonstrated mastery of CRISPR technology and somatic cell nuclear transfer in canids—a remarkable technical feat—the distinction between “de-extinction” and “designer proxy” is critical. True resurrection of an extinct species would require a complete, unbroken genome and reestablishment of its evolutionary lineage, neither of which is possible with highly degraded ancient DNA. Instead, Colossal’s wolves serve as ambitious proof-of-concepts for targeted conservation genetics, showcasing how precise genomic edits might bolster at-risk species—but stopping short of recreating the genuine dire wolf.