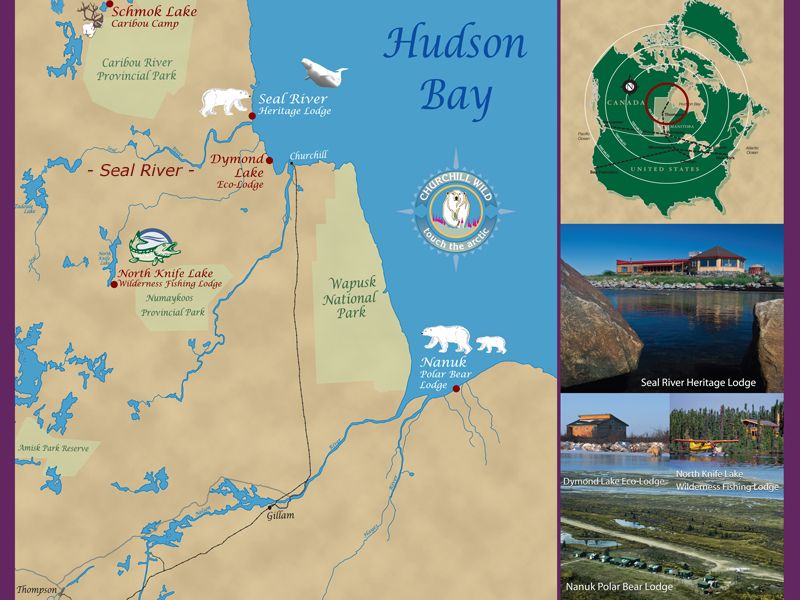

Where the Seal River meets the Hudson Bay there exists a hot spot for polar bears, seal, beluga whales and a myriad of Arctic wildlife – it is truly one of the world’s incredible natural beauties!

The area is rich in history and unique characteristics that make it one of the most desirable destinations for the world’s dedicated adventure travellers.

It is also a Canadian Heritage Rivers System.

Below is a “fact sheet” from the official website that outlines what makes this area so special.

:::::

Of the four major rivers in Northern Manitoba, the Seal River alone remains completely undeveloped, wild and rugged.

In contrast to the impoundments on the Churchill and the Nelson, and the rich fur trade and exploration history of the Hayes, the Seal River shows virtually no evidence of modern human activity. Although in the days before written history the river flowed through a major native hunting and fishing ground, the Seal now attracts only a few native people and small groups of hardy wilderness adventurers.

For these groups, travel downriver may require two to four weeks of difficult yet exhilarating boating. First, an extensive cold-water lake is encountered where winds can create dangerous waves; then, numerous long rapids in a totally isolated, sub-arctic environment test their survival skills; finally, travellers must navigate a boulder-strewn tidal estuary.

The Province of Manitoba nominated the Seal to the Canadian Heritage Rivers System in June, 1987. The nominated section is 260 km long and extends from the junction of the North and South Seal rivers, at Shethanei Lake, to Hudson Bay.

Geography

The Seal River is located in the roadless wilderness of Northern Manitoba, 1000 km by air charter from Winnipeg. The Seal estuary is 45 km across Hudson Bay from Churchill. Other than Churchill (population 1,300), the only settlement in the area is Tadoule (population 250), a small Chipewyan community located along the South Seal River at Tadoule Lake.

The Seal begins its course at Shethanei Lake ringed by the magnificent sand-crowned eskers that are so much a part of the Seal River landscape. Then, passing stands of black spruce, its velocity increases toward the Big Spruce River Delta, and accelerates dramatically into the rapids and gorges which surround Great Island. Beyond the island, the river leaves the boreal forest and enters a sparsely-treed, transitional subarctic environment of tundra and heath, christened by the natives the “Land of Little Sticks”. Finally, the Seal flows through barren arctic tundra, huge boulder fields and complex rapids, spilling into a beautiful estuary where its freshwaters mix with the salt of Hudson Bay.

Except for the less than two dozen skilled rafting and canoeing parties which visit the river each year, and the occasional native fisherman and trapper, there is virtually no human activity along the Seal River. The remote, roadless nature of this region has meant that activities such as mining exploration have been costly, air-supported ventures, and even the discussion stages of any development of the area’s hydro potential are many years away.

Natural Heritage

Nomination of the Seal River to the CHRS was based primarily on its outstanding natural heritage:

- The Seal is the largest remaining undammed river in Northern Manitoba.

- The river valley contains excellent representation of the subarctic boreal forest of the Precambrian Shield, and the arctic tundra of the Hudson Bay Lowlands.

- The valley is also habitat for 33 species of plants which are rare in Manitoba, and supports some unusually large white spruce and tamarack.

- Glacial features are everywhere. 300 metre-wide eskers extend up to several hundred kilometres in a north-south direction, sometimes as lake peninsulas or submerged landforms. Northern Manitoba’s largest drumlin fields were formed here by the glaciers, as were extensive boulder fields.

- The estuary area is actually rebounding from the weight of the glaciers at a rate of about 53 cm per century, among the fastest in the world.

- The Seal also provides habitat for undisturbed wildlife populations. Common here are moose, black bear, wolf, fox, snowshoe hare, ptarmigan, Canada goose, ducks, otter and beaver. The much rarer wolverine, golden and bald eagle, osprey, and polar bear are also found. Even more important, the river’s estuary is the calving and feeding grounds for 3000 beluga whales, part of the largest concentration in the world and the Seal is winter range for part of the 400,000 strong Kamanuriak caribou herd. (Editor’s Note: This is part of what makes Churchill Wild Safaris at the Seal River Heritage Lodge the best polar bear experience in the world! There is no better place on the Hudson Bay to see the belugas, polar bears and other Arctic wildlife.)

The Seal River area played an important role in native hunting, fishing and travelling. The white man found the area less hospitable. Isolated and difficult to navigate, with infertile soils and a cold climate, the Seal was quickly ruled out as a travel, trade or settlement corridor.

The river’s nomination to the CHRS was not based primarily on its human heritage, but there are several historical features of interest:

- The number of prehistoric artifacts and archaeological sites along the Seal is unusually large. Fire rings, scrapers, flakes, projectiles and hammers are often exposed on the surface of eskers at campsites and along the caribou trails by the river, between Tadoule and Great Island. The age of these finds spans the Paleo-Indian peoples of 7,000 years ago, to the Taltheili Tradition of 1 A.D. to 1700 A.D. (Editor’s Note: During our safaris guests often see tent rings, grave sites, fire pits as well as bone and tool fragments. This area was investigated and documented by archeologist Dr. Virginia Petch in the 1990’s)

- The remains of Chipewyan and European trappers’ cabins, and 100 year old grave sites marked by picket fences on top of eskers, reflect more recent occupation.

- The river is also closely associated with one European explorer. Samuel Hearne of the Hudson Bay Company left Fort Prince of Wales, near Churchill, in February 1771, on his second of three attempts to locate the copper fields which the Indians said bordered the northern ocean. Enduring incredible hardship, Herne followed the Seal River inland on foot to Shethanei Lake. He then back-tracked to the Wolverine River which he followed north into the barrenlands. Hearne became the first white man to discover the Arctic Ocean, and his journals and maps were a major contribution to the knowledge of Canada’s north until the early 20th century.

- An abandoned mining camp on Great Island, operated by the Great Seal Prospecting and Developing Syndicate between 1953 and 1958, is typical of mineral exploration camps which operated in the north during the 1940’s and 1950’s. Well preserved log buildings, a dynamite storage shack, a drilling platform, and other remnants are scattered throughout the site.

Recreation

The river’s nomination to the CHRS was based in part on its ability to provide an outstanding whitewater wilderness river trip. A trip from Tadoule to Hudson Bay would encounter, in order: 20 km of lake travel, with three major sets of rapids and a boulder field between Tadoule and Shethanei lake; 40 km of open, shallow water on Shethanei Lake, where dangerous waves and heavy winds can make travel impossible for days; 64 km of variable channels through numerous choppy rapids and a narrow, deep gorge; 28 km of intermittent whitewater along the scenic channel of Great Island including a possible 3 km portage; 124 km of flat country, transitional subarctic tundra forest and boulder field rapids; 4 km through the estuary’s maze of marshes, tidal flats, islands, shelves and reefs passable only on the north channel and then only when properly timed with the tides; and, finally a rendezvous with a float plane or water taxi from Churchill on the Hudson Bay shoreline.

In addition to a rugged wilderness river trip, the Seal River offers other recreational opportunities:

Shethanei Lake is very reliable for trophy-size lake trout, and large northern pike, and grayling are present throughout the river.

- Hikes to the top of eskers and rocky knolls are rewarded with 360 degree vistas of a totally natural environment. Short hikes along eskers and beaches, or across Great Island, allow modern-day explorers to follow the timeless migration path of the barren-ground caribou. Visitors can also retrace the steps of Samuel Hearne by climbing the esker that was his vantage point on Shethanei Lake.

- Wilderness camping is possible at numerous sites along the western two-thirds of the river. However, toward Hudson Bay, only poorly drained campsites on densely-willowed river banks are found.

:::::

To see the Seal River you can book any one of the following Churchill Wild Safaris: